If I had to pick two words that express San Francisco’s spirit, they would be freedom and beauty. And if I could add a qualifier it would be hard-earned.

We have led the nation and sometimes the world forward in its thinking and re-thinking of acceptance; and we that both need it and offer it gather here. Not because it’s the end of the rainbow, but rather because it is the very beginning. This, I feel, is at the heart of why our great city has grown, retained, and attracted such free-thinkers and artists. Here they join with others, leverage the freedom and respect they receive, and endure the hard work and struggle it requires to outwardly express their inner beauty.

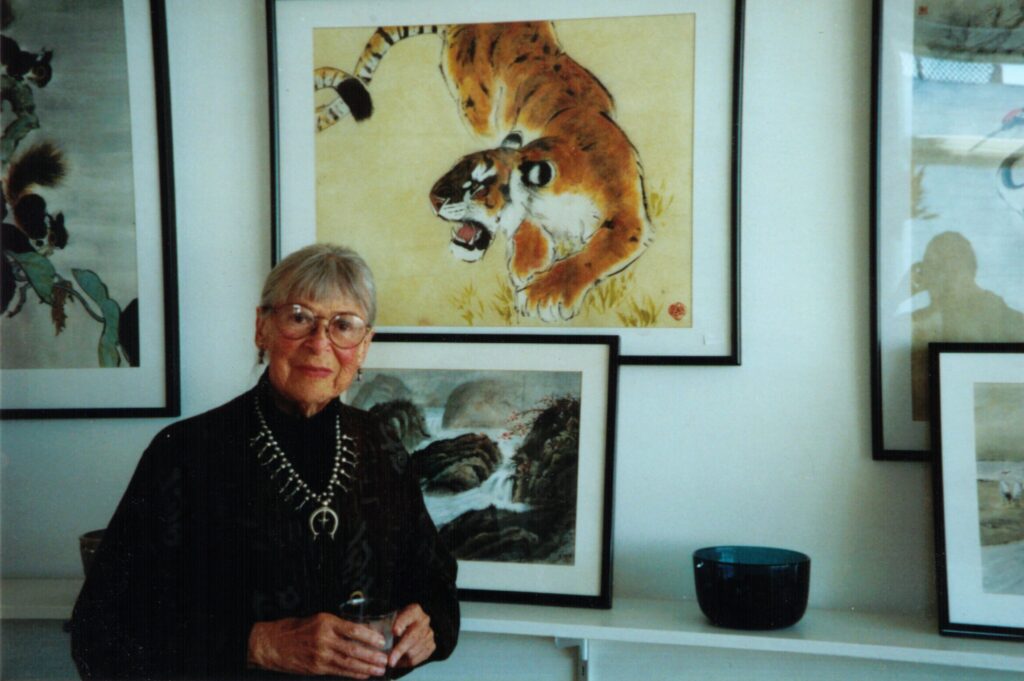

Eda Kavin’s life is just such an example – She is not only one of the great ladies of San Francisco, but also a great native artist who bloomed late in life. She bloomed because she finally could. She not only depended upon, but also loved and demanded her quest for freedom. And she was tireless in her enjoyment and expressions of art and beauty.

Here Eda touched many that have touched us; Yehudi Menuhin, Henry Miller, John Cage, Stephen Spender, and a generation of painters. Yet Eda herself never sought fame, and never taught – She did what she loved simply because she loved it. And yet she struggled very hard during her lifetime. From digging ditches in Russia to book binding, from McCarthyism to draftsman, from usher to artist. Hard-earned freedom indeed!

At 75 (1989), she enrolled in Professor Ming Ren’s Chinese Brush Painting class at City College — That she bloomed so quickly into such an accomplished artist was reason enough to bring a generation of his students to meet her.

But it is in her native roots that we experience her depth; and from there we can connect her art with her uniquely San Francisco story. For like The City itself, her life and art are a monument to what freedom, will power, and the quest for beauty can achieve.

-David Stein

Eda Kavin was one of the great ladies of San Francisco. She was a native born here to Russian immigrants who sold their Petaluma farm eggs at Fisherman’s Wharf. She was a calligrapher and book binder who fought back McCarthyism and proudly bound the banned books of Henry Miller. A draftsperson for the City for 27 years she created proclamations and even designed our first street parking permits.

At 75 she picked up a Chinese paint brush for the first time and in short order started creating exquisite paintings. She studied only with San Francisco City College’s Ming Ren, and for ten years his students would travel to her house to meet this lady who kept insisting “If I can do it, you can too.”

In May, 2004 when she was no longer able to paint or lunch with her friends, with gratitude she declared her life was over and died happily one month later.

Artist Biography – Eda Kavin (1914 – 2004)

“Usually, great art speaks for itself, yet Eda’s art also drew people to her. How could she come into my City College class at 75 years old with no background in Chinese brush painting, pick up an oriental brush for the first time and release such beauty?”

-Professor Ming Ren, San Francisco City College

Eda Kavin was born in Berkeley in 1914 to immigrant farmers Natia and Rebecca Kavin, who sold their Petaluma farm eggs at Fisherman’s Wharf. At the Wharf Eda met her lifelong friend, childhood sweetheart, and another great San Franciscan, violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Eda’s only sibling was her older sister Zena; who artist of note in Oakland and published with her husband Jon Cornin as “Corka”. Zena’s talent bloomed early, and sadly their mother believed there was only one talented child, so Eda’s artistic attempts were dismissed as “monkey-see, monkey-do”. As scarring as this was, Eda learned early that it was only herself she needed to please and it brought out her trademark determination.

Eda was graduated with straight A’s and perfect attendance from Lowell High School in 1933, and shortly thereafter her father sold the chicken farm, drove the family across country and they boated to Russia. He had been recruited by Stalin’s regime to teach farming to the homeland. Sensing trouble, Natia moved the family back after only a few years. Yet during their stay Eda translated for the local paper, dug ditches on farms, and returned home with many Russian friends and correspondents.

On returning Eda wanted to taste more of the world. She moved down to Los Angeles and lived with John Cage and other artists in Santa Monica, and then briefly to The Greenwich Village of New York City. But like so many of us who come to realize what is here, she returned as fast as she could.

In Berkeley in the late thirties her father built her a book binding studio in the basement of her sister’s house. She studied with Hazel Dreis and mastered book binding with a special fondness for the people and printings of San Francisco’s legendary Grabhorn press. She won several prizes and did prized works, attracting more alternative artists; among them Henry Miller. She bound his underground Tropic of Cancer (Miller was deemed obscene in the US) and his ground breaking Into The Night Life, which included many complicated (and explicit) illustrated pages on varied papers by Israeli artist Bezalel Schatz.

Eda learned calligraphy perhaps as early as High School, and during her book binding career her steady hand also penned many hand-written books. One such creation is her bound collection of Stephen Spender poems, now part of his estate’s collection.

In the late forties and into the fifties, Eda’s politics were forged against the hatred and suspicions of the House Un-American Activities Commission and McCarthyism, whose mushroom cloud of suspicion cut her off from her Russian friends and family. Eda joined other San Franciscans who never confused dissent with disloyalty, and The City became a crucial haven for those who had been blacklisted elsewhere. She often complained that after 9/11 our government’s patriotic suspicion had become worse than it was during the Cold War.

In the fifties Eda went to work for The City as a draftsperson in the City Planning department, retiring after 27 years. Beyond her drafting duties her calligraphy graced several resolutions, but perhaps her most widely seen design for The City is that of our first street parking permits. Yet her greatest design is that of her house on 19th Street, which she built from a vacant lot in 1957. Originally designed by Wurster, Bernardi and Emmons, it was far too expensive. She reworked the plans, dug out her own basement, and sharpened & organized the tools for the workers every night.

Never calling herself an artist until the end, she always expressed herself creatively crafting collages, holiday cards, thank-you notes, dinner place-cards, or even turning a mere check into a thing of beauty. She was also an insatiable lover of the arts, a tireless fan and patron of the Youth Orchestra and the Symphony Chorus, and for 25 years a volunteer usher at The Opera House.

At 75, Eda’s life and art would finally bloom. That year she obtained a reverse mortgage on her house, ‘retired’ from ushering and became a patron, bought her first new car, unleashed a passion for treating her loved ones to wonderful restaurants, and fate enticed her to sign up for a Chinese Brush Painting class at City College.

Taught by Professor Ming Ren, he insisted on being honest with his students; even beginners. “Keep trying” he would tell them, or if a student needed special encouragement he would say “Not too bad”. So it was stunning to both pupil and teacher when Eda’s first landscape scroll earned a “Pretty Good”.

Eda’s steady hand, deep grasp of detail, diligence and trademark determination combined with Ming Ren’s talent as both an artist and teacher to set her in motion. Eda quickly bloomed into a prolific artist in great command of her stroke; stunning even Asian artists. Her framers, refusing to believe that she was Caucasian, insisted on hand-delivering her first set of framed pictures in order to see the four-foot eleven inch ‘Tiger Woman’ for themselves. Over the course of her 15 remaining years she created approximately three hundred Chinese Paintings; many are considered exquisite.

Ming Ren uses examples of Eda’s work to show and encourage his students, and for ten years they made annual field trips to Eda’s home to meet and question the lady who said “If I can do this, you can too”. Only after a decade of painting did she finally accept her talent and allow herself to be called an artist. It took 79 years, but “monkey-see, monkey-do” was finally behind her.

Eda learned early to trust her intuition, and thus she always knew when it was time to let things go. When she could no longer lunch with her loved ones nor make it upstairs to paint, she announced her end was near. Her only remaining wish was to comfortably die in her home; which she accomplished on June 7, 2004.

Eda Kavin was one of the great ladies of San Francisco. And like The City itself, her life and art shine as a monument to what freedom, will-power, and the quest for beauty can achieve.

Obituary from San Francisco Chronicle, July 2004